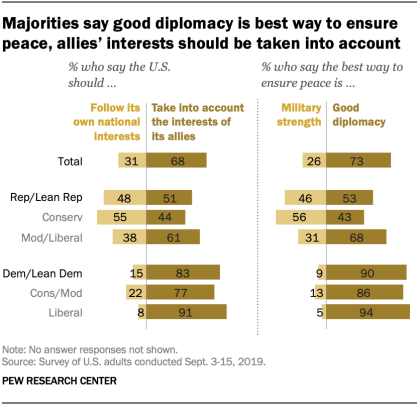

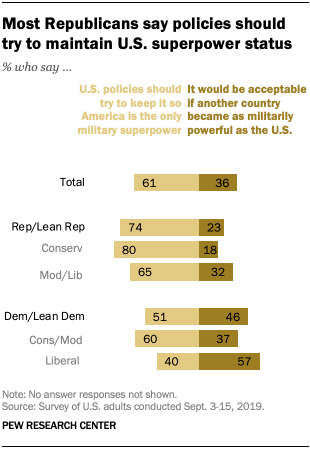

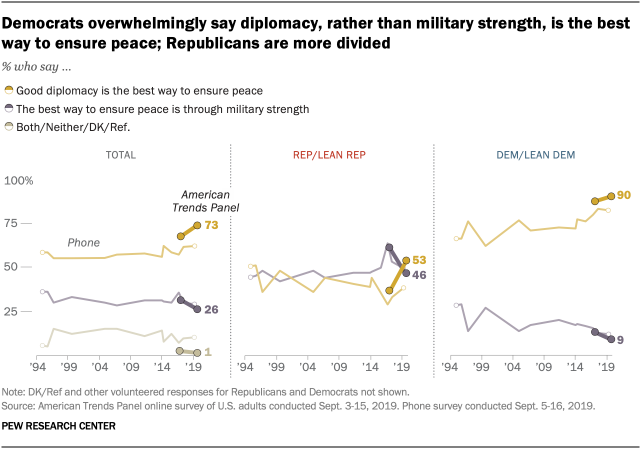

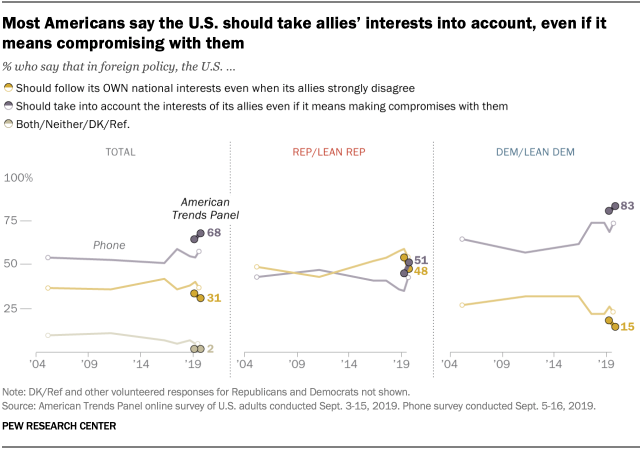

Roughly seven-in-ten Americans (73%) say that good diplomacy is the best way to ensure peace, while 26% say that military strength is the best way to do this. By a similar margin, more Americans say the U.S. should take the interests of allies into account, even if it means making compromises, than think the U.S. should follow its own national interests when allies disagree (68% vs. 31%).

There are stark partisan divides on both of these foreign policy values. Wide majorities of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents see good diplomacy as the best way to ensure peace (90%) and say the U.S. should take allies’ interests into account even if that results in compromises (83%).

By comparison, Republicans and Republican leaners are more divided in both of these views. About half (53%) see good diplomacy as the best means of ensuring peace, while 46% think military strength will best achieve this. The GOP split is nearly identical in views of how to consider allies’ interests: 51% say allies’ interests should be taken into account even if it means making compromises, while 48% say America’s national interests should be followed even if allies strongly disagree.

Ideological differences within the parties over foreign policy also are evident, particularly among Republicans. A narrow majority of conservative Republicans (56%) say military strength is the best way to ensure peace, while nearly seven-in-ten moderate and liberal Republicans place more importance on good diplomacy. Democrats are more consistent in their views, with overwhelming majorities of both conservative and moderate Democrats (86%) and liberal Democrats (94%) saying good diplomacy is the best way to ensure peace.

There is a similar pattern in views about whether the U.S. should take allies’ interests into account when there is disagreement: While 55% of conservative Republicans say the U.S. should follow its own national interests even when allies disagree, a 61% majority of liberal and moderate Republicans say the U.S. should take the interests of allies into account, even it it means making compromises.

Wide majorities of Democrats across the ideological spectrum favor taking allies’ interests into account, though liberals are more likely than conservatives and moderates to say this (91% vs. 77%).

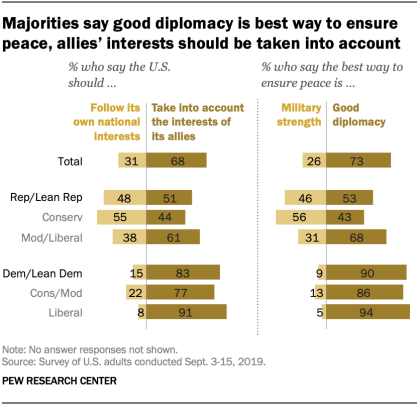

Overall, 53% of U.S. adults say “it’s best for the future of our country to be active in world affairs,” while 46% say “we should pay less attention to problems overseas and concentrate more on problems here at home.” Democrats are more likely than Republicans (62% vs. 45%) to say global engagement is best for the nation.

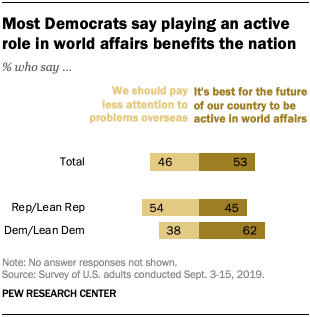

When it comes to America’s standing as a military superpower, 61% of the public thinks U.S. policies should try to keep it so America is the only military superpower, while 36% say it would be acceptable if another country became as militarily powerful as the U.S.

Republicans are particularly likely to say policies should focus on keeping the U.S. the only military superpower: Nearly three-quarters (74%) say this, while just 23% say it would be acceptable for another country to become as militarily powerful as the U.S. While conservative Republicans are somewhat more likely than moderate and liberal Republicans to say American foreign policy should prioritize maintaining singular superpower status (80% vs. 65%), this is the clear majority view among both ideological groups in the GOP.

Democrats are considerably more divided on this issue. Roughly half (51%) are in favor of U.S. policies that would maintain the country’s position as the only military superpower, while 46% say it would be acceptable for another country to become as militarily powerful as the U.S. There is a sizable ideological gap among Democrats in these views: 60% of conservative and moderate Democrats prioritize keeping America the only military superpower, while nearly the same share of liberal Democrats (57%) say it would be acceptable if another nation rivaled the U.S. for superpower status.

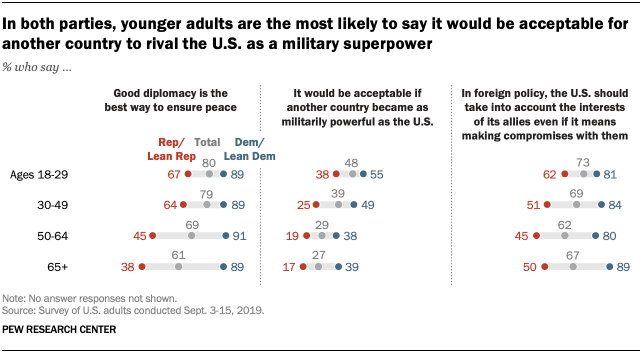

While majorities of adults in all age groups say the best way to ensure peace is through good diplomacy, those younger than 50 are more likely to hold this view than older Americans. And although about half of adults under 30 (48%) say it would be acceptable if another country became as militarily powerful as the U.S., only about a quarter of those 65 and older (27%) say the same. There are no substantial age differences in views of whether the U.S. should compromise with allies when there are foreign policy disagreements.

On all three of these measures of foreign policy values, there are substantial age divides within the GOP, while Democratic views differ little by age for two of the three questions.

About two-thirds of Republicans under 50 (65%) say that good diplomacy is the best way to ensure peace, while just 45% of those ages 50 to 64 and 38% of those 65 and older say the same. A similar trend in opinion is evident in views of the importance of America’s standing as a military superpower: Just 18% of Republicans ages 50 and older say it would be acceptable if another country became as militarily powerful as the U.S., compared with 25% of those ages 30 to 49 and nearly four-in-ten (38%) of those 18 to 29.

Younger and older Republicans differ modestly when it comes to views of allies’ interests in foreign affairs. Republicans under 30 are somewhat more likely than those in older age groups to favor compromising with allies when there is disagreement (62%, compared with about half of older Republicans).

In general, age differences in these foreign policy views among Democrats are less pronounced. Roughly nine-in-ten Democrats in all age groups say that good diplomacy, rather than military strength, is the best way to ensure peace. Similarly, eight-in-ten or more Democrats in all age groups say the U.S. should take allies’ interests into account in foreign policy, even if it means making compromises.

Younger Democrats are, however, more likely than older Democrats to express a willingness to see a country other than the U.S. become a military superpower: 55% of 18- to 29-year-old Democrats and about half of 30- to 49-year-old Democrats (49%) say this, compared with only about four-in-ten Democrats ages 50 and older.

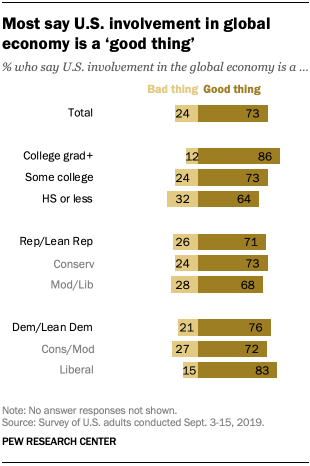

Nearly three-quarters of Americans say the country’s involvement in the global economy “is a good thing because it provides the U.S. with new markets and opportunities for growth,” while just 24% say “it is a bad thing because it lowers wages and costs jobs in the U.S.”

Republicans and Democrats offer similarly positive assessments of American involvement in the global economy. Majorities of all partisan and ideological groups say U.S. involvement in the global economy is a good thing; liberal Democrats are especially likely to take this view.

As in the past, attitudes toward U.S. involvement in the global economy are more positive among those with higher levels of educational attainment: 86% of those who have at least a four-year college degree say U.S. involvement a good thing. That compares with 73% of those who have completed some college, and a narrower majority (64%) of those who have not attended college.

In recent years, Pew Research Center has transitioned from probability-based telephone surveys to the American Trends Panel, a probability-based online panel. The transition from phone surveys conducted with an interviewer to online self-administered surveys brings with it the possibility of mode differences – differences arising from the method of interviewing.

This section includes opinion measures on whether the best way to ensure peace is through diplomacy or military strength; whether the U.S. should take into account the interests of allies or pursue its own national interests; and whether or not it is best for the future of the country to be active in world affairs. These measures, which have long-standing telephone trends, were included on a survey conducted in September on the American Trends Panel (ATP), on which this report is largely based, and a contemporaneous telephone survey. This allows for a comparison of any “mode effects” and places the current panel estimates in the context of telephone data.

Americans have long held the view that peace is best ensured though diplomacy rather than military strength. However, while nearly identical shares in both modes say military strength is the best way to ensure peace (26% on the ATP survey, 28% on the contemporaneous phone survey), the share saying good diplomacy is the best way to ensure peace is 11 percentage points higher in the online self-administered survey (73% vs. 62%). This is the result of a much lower share of people refusing the question in the online format, which is a common mode difference. The same pattern is seen in both parties.

As has been the case since 1994, when the question was first asked, far more Democrats than Republicans say diplomacy is the best way to ensure peace. On the ATP, 90% of Democrats and Democratic leaners express this view, compared with 53% of Republicans and Republican leaners.

Another long-standing trend (dating to 2004) is the question of whether the U.S. should take into account the interests of allies even if it means making compromises, or whether the U.S. should follow its own interests even when allies strongly disagree.

In the online survey, 68% say that in foreign policy the U.S. should take into account the interests of its allies, even if it means making compromises with them; a smaller share (31%) says the U.S. should follow its own national interests, even when its allies strongly disagree. In the phone survey, most also say the U.S. should take into account the interests of its allies, though by a somewhat narrower margin (59% to 36%). The partisan gap, which has been evident since this question was first asked, is nearly identical in the two formats (there’s a 32 percentage point gap between the shares of Republicans and Democrats who say allies’ interests should be taken into account in the online survey; in the telephone survey the partisan gap is 31 points).

In recent years, the public has been divided on whether it is best for the future of the U.S. to be active in world affairs, or to pay less attention to problems overseas and focus on problems in this country.

In the online survey, 53% say it is best to be active in world affairs, while 46% say less attention should be paid to overseas problems; in the phone survey, 48% say it is best for the U.S. to be active internationally and 47% prefer focusing on problems in this country. Partisan differences on this measure have increased in recent years; in the American Trends Panel survey, 62% of Democrats and 45% of Republicans say it is best for the U.S. to be active globally.